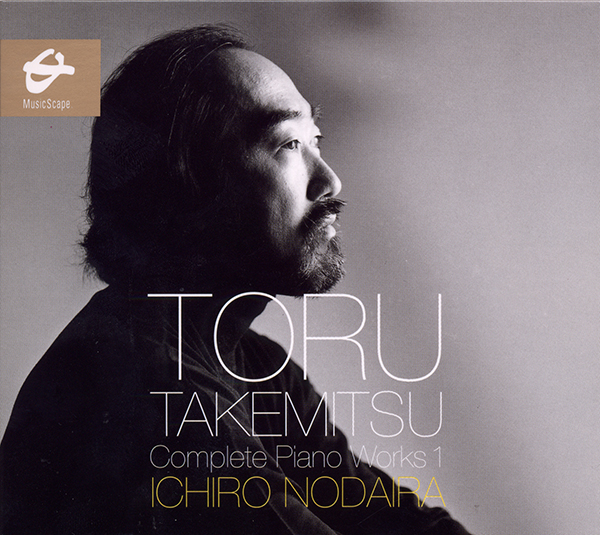

TORU TAKEMITSU: Piano Works

武満徹: ピアノ曲集

野平一郎(pf)

MSCD-0001 ¥2,530

「レコード芸術」特選

現代日本を代表する作曲家であり優れたピアニストでもある野平一郎の演奏による、武満徹ピアノ作品全集です。 ここでは「リタニ」から「雨の樹素描」までの幅広く知られた作品を収録。スコアに対する野平のあくまでも真摯な態度と深い分析、そして強固な構成力に支えられた繊細なタッチが、武満作品に新しい生命力を与え、これからの定盤足り得る名演奏となっています。

録音:1999年2月、秩父ミューズパーク音楽堂 プロデューサー/エンジニア: イシカワカズ

TORU TAKEMITSU Piano Works

Ichiro NODAIRA (pf)

MSCD-0001 ¥2,530

“Special Recomended CD of the month” ( Record Geijutsu Magazine )

As performed by Ichiro Nodaira an outstanding pianist and music composer representing modern Japan.

On this compilation,widery known compositions from “Litany” to “Rain Tree”and others and recorded. Nodaira’s sincerity and deep analysis of the music composition’s score, and his delicate touch of the piano supported by the strong composition has added new life to Takemitsu’s work. Nodaira’s perfomance of TORU TAKEMITSU Complete Works will become the established standard of future performances.

Recorded: Feb, 1999, Chichibu Muse Park

Producer/Engineer: Kaz Ishikawa

Liner notes:

Since his premature death in 1996, the works of Toru Takemitsu have been performed more frequently than ever. A great number of people miss Takemitsu and there have been many tribute performances and retrospective concerts in Japan. Deep respect has been paid to a truly international composer who, for the first time in the one hundred year history of Western music in Japan, is widely recognized and fully accepted by the Western musical community (i.e. composers, performers, publishers, music managements, and other music industries, as well as the great number of audiences).

Takemitsu’s charming personality attracted large numbers of people from different fields. The absence of Takemitsu for Japanese contemporary music not only means the absence of one of the greatest figures on the creative scene, but also the absence of a “spokesperson” who could appeal to a wide ranging public. It seems that the loss in the latter sense has been more critically damaging.

Considerable numbers of research papers and introductory books on Takemitsu have been published. This verifies that Takemitsu is regarded as one of the greatest composers not only in Japan but also in the West. However, an understanding of his music still appears insufficient. His pieces performed today are primarily from the late 1970s or thereafter when Takemitsu had established his style. This is even more evident with his orchestra pieces. November Steps, Requiem for Strings, and Dorian Horizon–all of which are from the late 1950s and 1960s–are the few exceptions. Such pieces as Solitude Sonore (Takemitsu’s first piece for large orchestra), Arc part I, and Arc part II (his greatest pieces of the 1960s) are hardly performed live despite the importance of these pieces. Incidentally, Arc part I and Arc part II “were” performed in a concert to celebrate Takemitsu’s sixtieth birthday in 1991. Unfortunately today, most listen to only a portion of his work. What is known about Takemitsu’s music is actually based on the repertoire “filtered” by someone else. Now is the time to begin reevaluating Takemitsu’s entire musical heritage without preconceptions.

Along with the guitar and flute, the piano was one of Takemitsu’s favorite instruments. From Lento in Due Movimenti (1950)–which was later “recomposed” and entitled Litany in 1989–to Rain Tree Sketch II (1992), Takemitsu wrote a number of pieces for this instrument throughout his career. Each of these pieces, receiving equal attention, has been performed quite frequently by numerous pianists. There have been many CD recordings of these works including several different editions of his “complete piano works.” Each of them is a fine unique production. It is notable that until now, Takemitsu has been the only Japanese composer that has been allowed this kind of luxury to such a degree.

It is known that aside from the pieces on his list of published compositions, Takemitsu–out of his attachment for the piano–wrote other works for the piano. These pieces have not been published or recorded. Breeze and Clouds (two short piano pieces for children) were written for a piano lesson program taught by Naoyuki Inoue on NHK television in 1979.

They were only published in the textbook used in the television program and have never been recorded on CD. Incidentally, Inoue performed many of Takemitsu pieces (though not the two short pieces mentioned above) at the Music Today Festival in 1978. The Nihon Kindai Ongaku-kan (an institute for modern Japanese music in Tokyo) has a copy of Romance for piano (1949). This piece, dedicated to Yasuji Kiyose, with whom Takemitsu studied composition, was recently premiered in 1998 at the Kioi Hall in Tokyo. In spite of its rough and straightforward expressions, Romance–having some sonic similarity to the first piece of Lento in Due Movimenti–is an attractive piece. In December 1998, Aki Takahashi premiered two entirely unknown pieces for piano from Takemitsu’s early period. As far as the piano pieces of his early period are concerned, new things are still being discovered.

Although the selection of the pieces recorded on this CD is similar to that of other “complete piano works” recordings, a future plan has been made to add Crossing and Corona (both graphically notated) as well as some of the unpublished or unrecorded pieces from his early period. In fact, Nodaira has already recorded Corona; nevertheless, it had to be excluded from this CD due to the limited recordable duration of the medium. However, careful attention needs to be paid in selecting which of the early pieces are to be recorded, because some of them might have been works that Takemitsu intended not to publicize.

Nodaira as a pianist is particularly excellent in producing a refined sonority from the piano and is able to grasp accurately the structure of the piece that he performs. He has been known for his extraordinary performances of well-structured serial pieces. On this CD recording, Nodaira, with his well-controlled pianism as well as his acute analytic abilities (which he probably acquired through his experiences of performing a great number of serial works) has successfully rendered a clear sonic contour to Takemitsu’s pieces. Avoiding simple soft-focus or overly fluid sonic images on which many pianists tend to rely, Nodaira vividly executes Takemitsu’s work with a clarity of sonic perspective and shadings. When Peter Serkin performs the second piece of Litany, the work perhaps more resembles Messiaen. The dignified voices (in the modes of limited transposition) simply converse with one another in clear and sharp contrasts. On the other hand, Nodaira in the recording of the same piece emancipates the sounds into a more delicate, sensitive sonic flow, though this flow is not excessively fluid. It is sometimes suspended, behaving ambiguously, and gazing back at its paths.

Because of the sensuality that Takemitsu’s sonic world possesses, performers quite often indulge themselves in the “atmosphere” of the piece, leaving their interpretations rather intuitive and emotional. Nodaira’s approach to Takemitsu’s work, on the other hand, is clear and objective. With this clear and objective approach, Nodaira not only perfectly realizes the clashes of sonic events and the occasional suspensions of the sonic fluidity, but also successfully brings out the surrealistic and the cruel from Takemitsu’s work. Such an example is heard in the second piece of Les yeux clos II, where the voices distributed in three staves are executed through an astonishingly well-controlled sonic perspective.

A rather unconventional notation is utilized in the first piece of the Uninterrupted Rest. Phrasings are indicated by beams that are occasionally broken. An isolated sixteenth rest, an accented note, or a non-accented chord is placed where the beams are broken, creating moments of silence or suspensions of sonic flow. Occasionally, the isolated rest at the broken beaming stands still against the sounds. At other times, it emerges from behind the sounds and disperses into them. When such events occur, the time flow is frozen. In Nodaira’s performance, what the breaks in beaming indicate are perfectly executed by the moments of silence or the suspensions of sonic flow. He, along with Yuji Takahashi, have been perhaps the only pianists thus far who achieve this to this extent. In Peter Serkin’s recording of the same piece, we experience the silence only where the rests are actually notated (thus, the function of the broken beams is more or less ignored). In Kumi Ogano’s recording, she even ignores the indicated rests in the score. Most of the interpretations by other pianists fall somewhere in-between these two extremes where the beams are treated only as a practical reference for rhythms and phrasings. The interpretations of Ichiro Nodaira and Yuji Takahashi, however, are clearly different. The function of the broken beams are carefully considered and accurately executed in their performances. I do not intend to be intrusive by pointing out the above.

I mention it here only to offer a possible reference for those who listen to this CD recording. Further judgments on Nodaira’s performance are naturally left open to each listener.

It is probably not a coincidence that both Nodaira and Takahashi are composer/pianists. They not only perform music, but also cogitate music, time, their origin and function, etc. By doing so, they are able to realize what Takemitsu truly intended in his work. Distancing Takemitsu’s piano work from an intuitive and emotional interpretive realm, where it has been enclosed for such a long time, and reexamining the scores carefully and accurately, Nodaira, the leading figure of the younger generation, has certainly launched out into a new world.

Seiji Choki

(translated by Hiroyuki Itoh with Steven Kazuo Takasugi)